NICOLET, Quebec — I’m sitting in an outdoor pen with four puppies chewing my fingers, biting my hat and hair, peeing all over me in their excitement.

At eight weeks old, they are two feet from nose to tail and must weigh seven or eight pounds. They growl and snap over possession of a much-chewed piece of deer skin. They lick my face like I’m a long-lost friend, or a newfound toy. They are just like dogs, but not quite. They are wolves.

When they are full-grown at around 100 pounds, their jaws will be strong enough to crack moose bones. But because these wolves have been around humans since they were blind, deaf and unable to stand, they will still allow people to be near them, to do veterinary exams, to scratch them behind the ears — if all goes well.

Yet even the humans who raised them must take precautions. If one of the people who has bottle-fed and mothered the wolves practically since birth is injured or feels sick, she won’t enter their pen to prevent a predatory reaction. No one will run to make one of these wolves chase him for fun. No one will pretend to chase the wolf. Every experienced wolf caretaker will stay alert. Because if there’s one thing all wolf and dog specialists I’ve talked to over the years agree on, it is this: No matter how you raise a wolf, you can’t turn it into a dog.

As close as wolf and dog are — some scientists classify them as the same species — there are differences. Physically, wolves’ jaws are more powerful. They breed only once a year, not twice, as dogs do. And behaviorally, wolf handlers say, their predatory instincts are easily triggered compared to those of dogs. They are more independent and possessive of food or other items. Much research suggests they take more care of their young. And they never get close to that Labrador retriever “I-love-all-humans” level of friendliness. As much as popular dog trainers and pet food makers promote the inner wolf in our dogs, they are not the same.

The scientific consensus is that dogs evolved from some kind of extinct wolf 15,000 or more years ago. Most researchers now think that it wasn’t a case of snatching a pup from a den, but of some wolves spending more time around people to feed on the hunters’ leftovers. Gradually some of these wolves became less afraid of people, and they could get closer and eat more and have more puppies, which carried whatever DNA made the wolves less fearful. That repeated itself generation after generation until the wolves evolved to be, in non-scientific terms, friendly. Those were the first dogs.

People must spend 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for weeks on end with wolf puppies just to assure them that humans are tolerable. Dog puppies will quickly attach to any human within reach. Even street dogs that have had some contact with people at the right time may still be friendly.

Despite all the similarities, something is deeply different in dog genes, or in how and when those genes become active, and scientists are trying to determine exactly what it is.

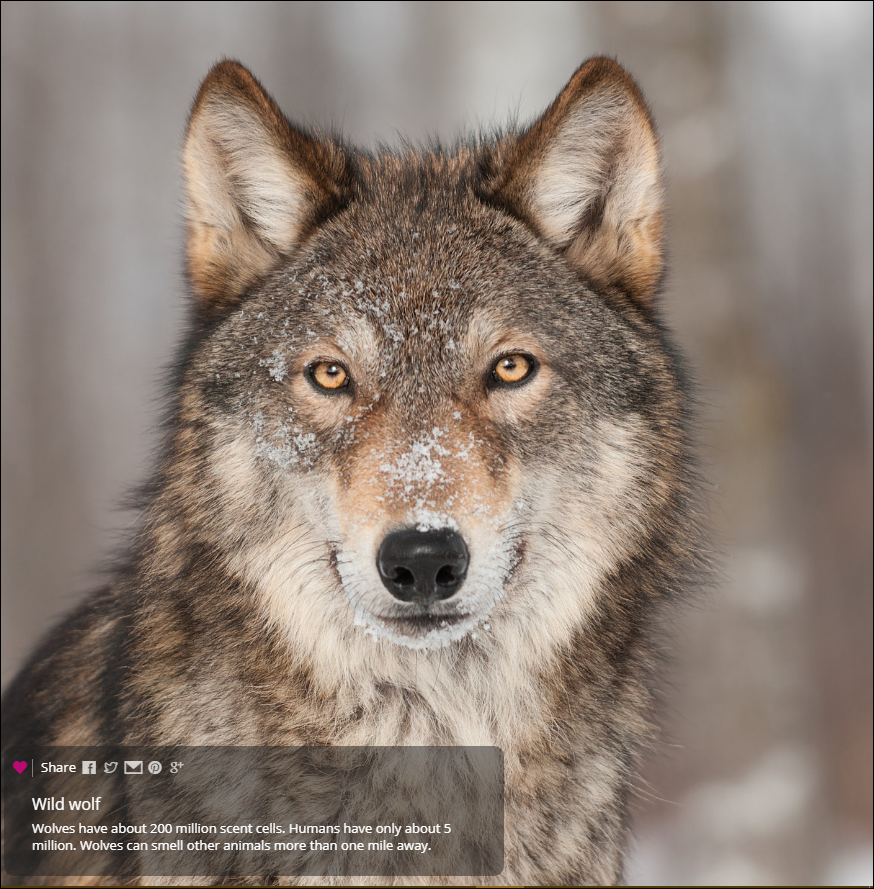

Wolf pups at Wolf Park, a 65-acre zoo and research facility in Battle Ground, Ind., in July. Though wolves and dogs are extremely similar genetically, their behaviors are very different — and scientists seek to find out why.

There are clues.

Some recent research has suggested that dog friendliness may be the result of something similar to Williams syndrome, a genetic disorder in humans that causes hyper-sociability, among other symptoms. People with the syndrome seem friendly to everyone, without the usual limits.

Another idea being studied is whether a delay in development during a critical socializing period in a dog’s early life could make the difference. That delay might be discovered in the DNA, more likely in the sections that control when and how strongly genes become active, rather than in the genes themselves.

This is research at its very beginning, a long shot in some ways. But this past spring and summer, two scientists traveled to Quebec to monitor the development of six wolf pups, do behavior tests and take genetic samples. I followed them.

I visited other captive wolves as well, young and adult, to get a glimpse of how a research project begins — and, I confess, to get a chance to play with wolf puppies.

I wanted to have some firsthand experience of the animals I write about, to look wolves in the eye, so to speak. But only metaphorically. As I was emphatically told in a training session before going into an enclosure with adult wolves, the one thing you definitely do not do is look them in the eye.

From left, Kathryn Lord, Michele Koltookian and Diane Genereux, of the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester and the Broad Institute in Cambridge, at the Zoo Académie, a combination zoo and training facility in Nicolet, Quebec

Wolf pups at play at Zoo Académie. Researchers wonder whether a delay in social development in a dog’s early life could explain the difference between wolves and dogs, and they’re looking to DNA for the answer.

Sleeping With Wolves

Zoo Académie is a combination zoo and training facility here on the southern bank of the St. Lawrence River, about two hours from Montreal. Jacinthe Bouchard, the owner, has trained domestic and wild animals, including wolves, all over the world.

This past spring she bred two litters of wolf pups from two female wolves and one male she had already at the zoo. Both mothers gave birth in the same den around the same time at the beginning of June. Then unusually bad flooding of the St. Lawrence threatened the den, so Ms. Bouchard had to remove them at about seven days old instead of the usual two weeks.

Then began the arduous process of socializing the pups. Ms. Bouchard and her assistant stayed day and night with the animals for the first few weeks, gradually decreasing the time spent with them after that.

On June 30, Kathryn Lord and Elinor Karlsson showed up with several colleagues, including Diane Genereux, a research scientist in Dr. Karlsson’s lab who would do most of the hands-on genetics work.

Dr. Lord is part of Dr. Karlsson’s team, which splits time between the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester and the Broad Institute in Cambridge. Their work combines behavior and genetic studies of wolf and dog pups.

An evolutionary biologist, Dr. Lord is an old hand at wolf mothering. She has hand-raised five litters.

“You have to be with them 24/7. That means sleeping with them, feeding them every four hours on the bottle, ” Dr. Lord said.

Also, as Ms. Bouchard noted, “we don’t shower” in the early days, to let the pups get a clear sense of who they are smelling.

Dr. Genereux, right, and Ms. Koltookian at the Zoo Académie.

Dr. Genereux, right, and Ms. Koltookian with the wolf pups. The researchers say the odds of being able to pin down genetically the critical shift from helplessness in infancy to being able to explore the world around them are long, but still worth pursuing.

That’s very important, because both wolves and dogs go through a critical period as puppies when they explore the world and learn who their friends and family are.

With wolves, that time is thought to start at about two weeks, when the wolves are deaf and blind. Scent is everything.

In dogs, it starts at about four weeks, when they can see, smell and hear. Dr. Lord thinks this shift in development, allowing dogs to use all their senses, might be key to their greater ability to connect with human beings.

Perhaps with more senses in action, they are more able to generalize from tolerating individual humans with a specific scent to tolerating humans in general with a scent, sight and sound profile.

When the critical period ends, wolves, and to a lesser extent dogs, experience something like the onset of stranger anxiety in human babies, when people outside of the family suddenly become scary.

The odds of being able to pin down genetically the shift in this crucial stage are still long, but both Dr. Lord and Dr. Karlsson think the idea is worth pursuing, as did the Broad Institute. It provided a small grant from a program designed to support scientists who take leaps into the unknown — what you might call what-if research.

There are two questions the scientists want to explore. One, said Dr. Karlsson: ”How did a wolf that was living in the forest become a dog that was living in our homes?”

The other is whether fear and sociability in dogs are related to the same emotions and behaviors in humans. If so, learning about dogs could provide insights into some human conditions in which social interaction is affected, like autism, or Williams syndrome, or schizophrenia.

The pups at Zoo Académie were only three weeks old when the group of researchers arrived. I showed up the next morning and walked into a room strewn with mattresses, researchers and puppies.

The humans were still groggy from a night with little sleep. Pups at that age wake up every few hours to whine and paw any warm body within reach.

Wolf mothers prompt their pups to urinate and defecate by licking their abdomens. The human handlers massaged the pups for the same reason, but often the urination was unpredictable, so the main subject of conversation when I arrived was wolf pup pee. How much, on whom, from which puppy.

As soon as I walked in, I was handed a puppy to cradle and bottle-feed. The puppy was like a furry larva, persistent, single-minded, with an absolute intensity of purpose.

Even with fur, teeth and claws, the pups were still hungry and helpless, and I couldn’t help but remember holding my own children when they took a bottle. I suspect that tiger kittens and the young of wolverines are equally irresistible. It’s a mammal thing.

A wolf pup, inside a pen, observing a borzoi outside at the Zoo Académie. The critical exploratory phase for wolves is thought to start at about two weeks, when wolf pups are still deaf and blind — scent is their primary sense. With dogs, that period begins at about four weeks, when they can see, smell and hear.

The first part of Dr. Lord’s testing was to confirm her observations that the critical period for wolves starts and ends earlier than that for dogs.

She set up a procedure for testing the pups by exposing them to something they could not possibly have encountered before — a jiggly buzzing contraption of bird-scare rods, a tripod and a baby’s mobile.

Each week she tested one pup, so that no pup got used to it. She would put the puppy in a small arena, with low barriers for walls and with the mobile turned on. She would hide, to avoid distracting the puppy. Video cameras recorded the action, showing how the pups stumbled and later walked around the strange object, or shied away from it, or went right up to sniff it.

At three weeks, the pups had been barely able to get around and were still sleeping almost every minute they weren’t nursing. By eight weeks, when I returned to have them gambol all over me, they were rambunctious and fully capable of exploration.

The researchers won’t publicize the results until observers who never saw the puppies view and analyze the videos. But Dr. Lord said that wolf experts considered eight-week-old wolf puppies past the critical period. They were so friendly to me and others because they had been successfully socialized already.

Before and after the test, she collected urine, to measure levels of a hormone called cortisol, which rises during times of stress. If the pup in the video would not approach the jiggly monster and cortisol levels were high, that would indicate that the pup had begun to experience a level of fear of new things that could stop exploration. That would confirm the timing of the critical period.

Dr. Lord letting an eight-week-old wolf pup investigate the jiggly monster testing contraption she devised.

She and Dr. Karlsson and others from the lab also collected saliva for DNA testing. They planned to use a new technique called ATAC-seq that uses an enzyme to mark active genes. Then when the wolf DNA is fed into one of the advanced machines that map genomes, only the active genes would be on the map.

Dr. Genereux, who was isolating and then reading DNA, said she thought it was “a long shot” that they would find what they wanted. She and the other researchers plan to refine their techniques to ask the questions successfully.

When They Grow Up

And what are socialized wolves like when they grow up, once the mysterious genetic machinery of the dog and wolf direct them on their separate ways?

I also visited Wolf Park, in Battle Ground, Ind., a 65-acre zoo and research facility where Dana Drenzek, the manager, and Pat Goodmann, the senior animal curator, took me around and introduced me not only to puppies they were socializing, but to some adult wolves.

Timber, a mother of some of the pups at Wolf Park in Indiana.

In the 1970s, Ms. Goodmann worked with Erich Klinghammer, the founder of Wolf Park, to develop the 24/7 model for socializing wolf puppies, exposing them to humans and then also to other wolves, so they could relate to their own kind but accept the presence and attention of humans, even intrusive ones like veterinarians.

The sprawling outdoor baby pen was filled with cots and hammocks for the volunteers, since the wolves were now nine and 11 weeks old and living outdoors all the time. There were plastic and plywood hiding places for the wolves and plenty of toys. It looked like a toddlers’ playground, except for the remnants of their meals — the odd deer clavicle or shin bone, and other assorted ribs, legs and shoulder bones, sometimes with skin and meat still attached.

The puppies were extremely friendly with the volunteers they knew and mildly friendly with me. The adult wolves I met were also courteous, but remote. Two older males, Wotan and Wolfgang, each licked me once and walked away. Timber, the mother of some of the pups, and tiny at 50 pounds, also investigated me and then retired to a platform nearby.

Only Renki, an older wolf who had suffered from bone cancer and now got around on three legs, let me scratch his head for a while. None was bothered by my presence. None was more than mildly interested. None seemed to realize or care about my own intense desire to see the wolves, be near them, learn about them, touch them.

Pat Goodmann, the senior animal curator at Wolf Park.

A mobile of animal bones hangs over the nursery where pups at Wolf Park live until aged 5-6 weeks.

I saw how powerfully a visit with wolves could affect how you feel about the animals. I wanted to come back and help raise pups, and keep visiting so that I could say an adult wolf knew me in some way.

But I also wondered whether it was right to keep wolves in this setting. In the wild, they travel large distances and kill their food. These wolves were all bred in captivity and that was never a possibility for them.

But was I simply indulging a fantasy of getting close to nature? Was this in the same category as wanting a selfie with a captive tiger? What was best for the wolves themselves?

I asked Ms. Goodmann about it. She said that park operated on the idea that getting to know the park’s wolves, which had never been deprived of an earlier life in the wild, would make visitors care more for wild wolves, for conservation, for preserving a life for wild carnivores that they could never be part of.

And she noted that Wolf Park operates as a combination zoo and research station. Students and others from around the world compete to work as interns, helping with everything from raising puppies to emptying the fly traps.

This is the rationale for all zoos, and it was a strong argument. Then she made it stronger. She pointed out that one of the interns, Doug Smith, worked on the reintroduction of wild wolves to Yellowstone National Park.

Dana Drenzek, manager of Wolf Park, with a pup.

Haley Gorenflo, a volunteer at Wolf Park, howling with adolescent wolves.

Dr. Smith has had a major role in the Wolf Restoration Project from the very beginning in 1995 and has been project leader since 1997. I reached him one morning at his office at park headquarters and asked him about his time as an intern at Wolf Park.

“I hand-reared four wolf pups, sleeping with them on a mattress for six weeks,” he said. “It had a profound effect. It was the first wolf job I ever got in my life. It turned into my career.”

From there he went on to study wild wolves on Isle Royale in Michigan, and then to work with L. David Mech, a pioneering wolf biologist who is a senior scientist with the U.S. Geological Survey and an adjunct professor at the University of Minnesota. Eventually, he went to Yellowstone to work on restoring wolves to the park.

He said ethical questions about keeping wild animals in captivity are difficult, even when every effort is made to enrich their lives. But places like Wolf Park provide great value, he said, if they can get people “to think about the plight of wolves across the world, and do something about it.”

In today’s environment, “with conservation on the run, nature on the run, you need them,” he added.

Then he said what all wolf specialists say: That even though wolf pups look like dogs, they are not, that keeping a wolf or a wolf-dog hybrid as a pet is a terrible idea.

“If you want a wolf,” he said, “get a dog.”

Dozing at Zoo Académie in Quebec.

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/55/96/55965676-73ed-4de4-b090-e3dfa280739e/a-263-0138.jpg)